In a world in which global poverty affects almost half the population, microfinance has gained a great deal of momentum in recent years because it has proven itself over time to be an effective poverty-alleviation tool. Traditionally, the microfinance industry has been a non-profit movement geared toward helping the poor rise from poverty through the provision of small loans to create or expand businesses. However, the need for additional funding capital and the growing popularity of the industry have spurred an industry-wide debate between the traditional non-profit model and the newer for-profit microfinance model ideas.

Poverty alleviation methods began as solely charity-based approaches in the 1960s as the first humanitarian crises reached mass audiences on television. The world watched through their TV as families died of starvation in places like Biafra, an oil-rich area that had seceded from Nigeria and was being blockaded by the Nigerian government. The level of foreign aid distributed around the world soared from the 1960s, peaking at the end of the Cold War. Live Aid music concerts raised public awareness about challenges like starvation in Africa, while the United States launched major, multi-billion-dollar aid initiatives, and the World Bank and advocates of aid aggressively seized on research claiming foreign aid led to economic development. But not everyone was convinced.

Angus Deaton, an economist at Princeton University who studied poverty in India and South Africa and spent decades working at the World Bank, argued that, by trying to help poor people in developing countries, we may actually be corrupting those nations’ governments and slowing their growth. According to Deaton and the economists who agree with him, much of the aid that the world’s developed countries have spent may not have ended up helping the poor. It’s based on the false assumption that if you simply give money to people they will not be poor anymore.

In the 1970s, several organizations developed very similar models that spawned the microfinance movement. Probably the best-known example is that of economics lecturer Muhammed Yunus at the University of Chittagong, Bangladesh. He lent $27 to a group of impoverished women to grow their bamboo stool business and break out Another early and quite entertaining example is that of John Hatch who was implementing a lending program in Bolivia in 1972. The program had $1 million in cash when hyperinflation struck, and the local currency tanked precipitously. Mr. Hatch and his team had to disburse loans as quickly as they could to protect the project from hyperinflation. They lent the money to self-selecting lending groups that they dubbed communal banks in which everyone co-signed on each other’s loans, which gave the team some confidence of who was most trusted in a community. They drove around Bolivia with a truck full of cash disbursing loans in the morning and getting out of town so that thieves would not know where they were. The team slept in the back of the truck on top of the cash. Mr. Hatch claims that he came up with the idea of communal banks on a flight to Bolivia after his fourth bourbon. We can only hope that is true.

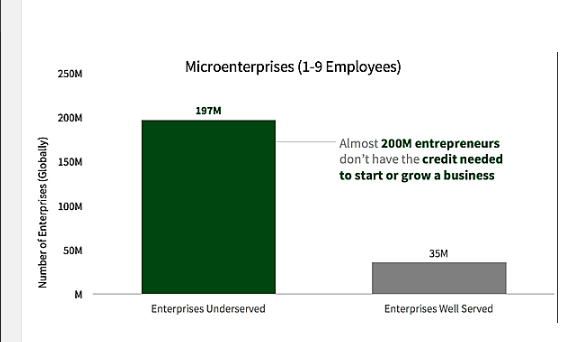

Microfinance was born from these and other efforts and quickly created a record of success not just in promoting financial resilience but in achieving other social objectives like reaching the excluded, empowering women, and developing the capacity of small groups of people to take control of their own lives. Many others followed suit, and today the World Bank estimates that more than 35 million people are served by some 7,000 microfinance institutions all over the world. Funds have been donated, lent out, and repaid in a constant cycle of dollar signs and percents; and a quick glance at the numbers will show that this non-profit model has helped create millions of businesses and strengthen just as many communities over the last few decades.

But the funds contributed by global philanthropy, even when combined with the development or aid budgets of many national governments (themselves facing budget constraints), add up to mere billions. The cost of solving the global need for credit runs into the hundreds of billions. According to the World Bank, there are still 200 million micro-entrepreneurs who still do not have access to credit, and in terms of dollars, this amounts to upwards of 1.4 trillion dollars. A need, that many argue, is not going to be met with deep pockets and donations.

In 2011, meanwhile, some $212 trillion existed in the world’s financial stock market (comprising equity market capitalization and outstanding bonds and loans) and in the next 40 years, some estimate, Generation X and Millennials could inherit up to $41 trillionfrom Baby Boomers. Unlocking even a small percentage of this capital would expand the resources available to address the world’s biggest credit problems dramatically.

Capital markets, however, do not do warm and fuzzy things. Capital markets go where there are returns. If one is to have any hope of solving the increasingly dynamic, complex and messy challenges that come with lack of credit one needs a model that offers returns, one needs a for profit model.

Of course, we are not suggesting for-profit microfinance replace charitable donations, government spending, or philanthropic grants. Rather, we are suggesting a need for more and different types of for-profit microfinance funds to leverage larger and more commercial sources of funding. As the pool of microfinance investors grows, their investments will make it easier for entrepreneurs with demonstrated track records to tap into a far larger source of funding: a portion of the trillions of dollars of mainstream investment funds in global capital markets.

As more impact investors, ranging from individuals to pension funds, seek to fund talented, innovative, and committed entrepreneurs and successful local business, they can play a role in the creation of sustainable livelihoods and the strengthening of communities. When microfinance becomes a viable component of impact investors’ portfolios, microfinance will have access to investment dollars, which is a far larger pool of financial resources than philanthropic dollars. The opportunities provided to low-income people can become true game-changers. This is the possibility of for-profit microfinance and the possibility of impact investing.

The question at this point is: what’s next? In any evolving marketplace, with excitement comes confusion. If you have questions or like to learn more please visit our homepageand see the impact for-profit microfinance is already having.